Business Ownership and Management

The Importance of Proper Pricing

Pricing is one of those things that can make or break a company. Doing it right takes an understanding of your business (cost structure and growth / profitability goals), the market, your competition, and more. Doing it wrong can mean the death of your business (fast or slow), the inability to attract and retain the best talent, as well as creating a situation where you will no longer have the opportunity to reach your full potential.

These problems apply to companies of all sizes – although large organizations are often better positioned to absorb the impact of bad pricing decisions or sustain an unprofitable business unit. Understanding all possible outcomes is an important aspect of pricing related to risk and risk tolerance.

When I started my consulting company in 1999, we planned to win business by pricing our services 10%-15% lower than the competition. It was a bad plan that didn’t work. Unfortunately, this approach is something you see all too often in businesses today.

We only began to grow after increasing our prices (about 10% more than the competition) and focused on justifying that with our expertise and the value provided. We were (correctly) perceived as a premium alternative, and that positioning helped us grow.

Several years ago, I had a management consulting engagement with a small software company. The business owner told me they were “an overnight success 10 years in the making.” His concern was that they might not be able to capitalize on recent successes, so he was looking for an outside opinion.

I analyzed his business, product, customers, and competition. His largest competitor is the industry leader in this space, and products from both companies were evenly matched from a feature perspective. My client’s product even had a few key features that were better for management and compliance in Healthcare and Union environments that his larger and more popular competitor lacked. So, why weren’t they growing faster?

I found that competition was priced 400% higher for the base product. When I asked the owner, he told me their goal was to be priced 75% – 80% less than the competition. He could not explain why he did this other than to state that he believed that his customers would be unwilling to pay any more than that. His lack of confidence in his product became evident to companies interested in his solution.

He often lost head-to-head competition against that competitor, but almost never on features. Areas of concern were generally the size and profitability of the company and the risk created by each for prospects considering his product.

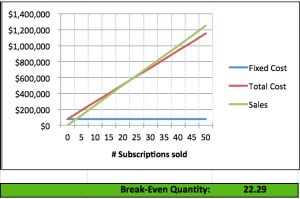

I shared the graph (below) with this person, explaining how proper pricing would increase their profitability and annual revenue and how both of those items would help provide customers and prospects with confidence. Moreover, this would allow the company to grow, eliminate single points of failure in key areas (Engineering and Customer Support), add features, and even spend money on marketing. Success breeds success!

In another example, I worked with the Product Manager of a large software company responsible for producing quarterly product package distributions. This work was outsourced, and each build cost approximately $50K. I asked, “What is the break-even point for each distribution?” That person replied, “There really isn’t a good way to tell.”

By the end of the day, I provided a Cost-Volume-Profit (CVP) analysis spreadsheet that showed the break-even point. Even more important, it showed the contribution margin and demonstrated there was very little operating leverage provided these products (i.e., they weren’t very profitable even if you sold many of them).

My recommendations included increasing prices (which could negatively impact sales), investing in fewer releases per year, or finding a more cost-effective way of releasing those products. Without this analysis their “business as usual” approach would have likely continued for several years.

Companies are in business to make money – pure and simple. Everything you do as a business owner or leader needs to be focused on growth. Growth is the result of a combination of factors, such as the uniqueness of the product or services provided, quality, reputation, efficiency, and repeatability. Many of these are the same factors that also drive profitability. Proper pricing can help predictably drive profitability, and having excess profits to invest can significantly impact growth.

Some customers and prospects will do everything possible to whittle your profit margins down to nothing. They are focused on their own short-term gain and not on the long-term risk created for their suppliers. Those same “frugal” companies expect to profit from their own business, so it is unreasonable to expect anything less from their suppliers.

My feeling is that “Not all business is good business,” so it is better to walk away from bad business in order to focus on the business that helps your company grow and be successful.

One of the best books on pricing I’ve ever found is “The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing: A Guide to Profitable Decision Making” by Thomas T. Nagle and Reed K. Holden. I recommend this extremely comprehensive and practical book to anyone responsible for pricing or with P&L responsibility within an organization. It addresses the many complexities of pricing and is truly an invaluable reference.

In a future post, I will write about the metrics I use to understand efficiency and profitability. Metrics can be your best friend when optimizing pricing and maximizing profitability. This can help you create a systematic approach to business that increases efficiency, consistency, and quality.

At my company we developed a system where we know how long common tasks would take to complete, and had efficiency factors for each consultant. This allowed us to create estimates based on the type of work and the people most likely to work on the task and fix-bid the work. Our bids were competitive, and even when we were the highest-priced bid we often won because we would be the only (or one of the few) companies to guarantee prices and results. Our level of effort estimates were +/- 4%, and that helped us maintain a 40%+ minimum gross margin for every project. This analytical approach helped our business double in revenue without doubling in size.

There are many causes of poor pricing, including a lack of understanding of cost structure; Lack of understanding of the value provided by a product or service; Lack of understanding of the level of effort to create, maintain, deliver, and improve a product or service; and Lack of concern for profitability (e.g., salespeople who are paid on the size of the deal, and not on margins or profitability).

But, with a little understanding and effort, you can make small adjustments to your pricing approach and models that can have a huge impact on your business’s bottom line.

Lessons Learned from Small Business Ownership

I learned many valuable lessons over the course of the 8+ years that I owned my consulting business. Many were positive, a few were negative, but all were educational. These lessons shaped my perceptions about and approaches to business, and have served me well. This post will just be the first of many on the topic.

My lessons learned covered many topics: How to structure the business; Business Goals; Risk; Growth Initiatives and Investment; Employees and Benefits; Developing a High-Performance Culture; Marketing and Selling; Hiring and Firing; Bringing in Experts; Partners and Contractors; The need to let go; Exit Strategies and more.

In my case these lessons learned were compounded by efforts to start a franchise for the consulting system we developed, and then our expansion to the UK with all of the challenges associated with international business.

It’s amazing how more significant those lessons are (or at least feel) when the money is coming out of or going into “your own pocket.” Similar decisions at larger companies are generally easier, and (unfortunately) often made without the same degree of due diligence. Having more “skin in the game” does make a difference when it comes to decision making and risk.

Businesses are usually started because someone is presented with a wonderful opportunity, or because they feel they have a great idea that will sell, or because they feel that they can make more money doing the same work on their own. Let me start by telling you that the last reason is usually the worst reason to start a business. There is a lot of work to running a business, a lot of risk, and many expenses that most people never consider.

I started my business because of a great opportunity. There were differences of opinion about growth at the small business I was working for at the time, and this provided me with the opportunity to move in a direction that I was more interested in (shift away from technical consulting and move towards business / management consulting). Luckily I had a customer (and now good friend) who believed in my potential and the value that I could bring to his business. He provided both the launch pad and safety net (via three month initial contract) that I needed to embark on this endeavor. For me the most important lesson learned is to start a business for the right reasons.

More to come. And, if you have questions in the meantime just leave a comment and I will reply. Below are some of the statistics on Entrepreneurship that can be pretty enlightening:

Bureau of Labor Statistics stats on Entrepreneurship in the US

Diamonds or just Shiny Rocks?

During a very candid review years ago, my boss at the time (the CEO of the company) made a surprising comment to me. He said, “Good ideas can be like diamonds – drop them occasionally, and they have a lot of value. But sprinkle them everywhere you go, and they just become a bunch of shiny rocks.” This was not the type of feedback that I was expecting, but it turned out to be both insightful and very valuable.

For a long time, I have held the belief that there are four types of people at any company: 1) People who want to make things better; 2) People who are interested in improvement but only in a supporting role; 3) People who are mainly interested in themselves (they can do great things, but often at the expense of others); and 4) People that are just there and don’t care much about anything. This opinion is based on working and consulting at many companies over a few decades.

A recent Gallup Poll stated Worldwide only 13% of Employees are “engaged at work” (the rest are “not engaged” or “actively disengaged”). This is a sad reflection of employees and work environments if it is true. Since it is a worldwide survey, it may be highly skewed by region or industry and, therefore, not indicative of what is typical across the board. Those results were not completely aligned with my thinking but were interesting nonetheless.

So, back to the story…

Before working at this company, I had run my own business for nearly a decade and was a consultant for 15 years, working at large corporations and startups. I am used to taking the best practices learned from other companies and engagements and incorporating them into our business practices to improve and foster growth.

I take a systemic view of business and see the importance of optimizing all components of “the business machine” to work harmoniously. Improvements in one area ultimately positively impact other areas of the business. From my naive perspective, I was helping everyone by helping those who have easily solved problems.

I learned that while trying to be helpful, I was insensitive to the fact that my “friendly suggestions based on past success” stepped on other people’s toes, creating frustration for those I intended to help. Providing simple solutions to their problems reflected poorly on my peers.

Suggestions and examples that were intended to be helpful had the opposite effect. Even worse, it was probably just as frustrating to me to be ignored as it was to others to have me infringe on their aspect of the business. The resulting friction was very noticeable to my boss.

Those ideas (“diamonds”) may have been considered had I been an external consultant. But as part of the leadership team, I was coming across as someone just interested in themselves (leaving “shiny rocks” laying around for people to ignore or possibly trip over).

Perception is reality, and my attempts to help were hurting me. Luckily, I received this honest and helpful feedback early in this position and was able to turn those perceptions around.

What are the morals of this story?

First, people who are engaged have the greatest potential to make a difference. Part of being a business leader is making sure that you have the best possible team, and are creating an environment that challenges, motivates, and fosters growth and accountability.

Disengaged employees or people who are unwilling or unable to work with/collaborate with others may not be your best choices, regardless of their talent. They could actually be detrimental to the overall team dynamics.

Second, doing what you believe to be the right thing isn’t necessarily the best or right way to approach something. Being sensitive to the big picture and testing whether or not your input is being viewed as constructive was a big lesson learned for me. If you have good ideas but are ineffective, consider that your execution could be flawed. Self-awareness is very important.

Third, use your own examples as stories to help others understand potential solutions to problems non-threateningly. Let them connect to their own problems, helping them become more effective and allowing them to save face. It is not a competition. And, if someone else has good ideas, help support them through collaboration. In the end, it should be more about effectiveness, growth, and achievement of business goals than who gets the most credit.

While this seems like common sense now, my background and personal biases blinded me to that perspective.

My biggest lesson learned was about adaptation. There are many ways to be effective and make a difference. Focus on understanding the situation and its dynamics to employ the best techniques, which is ultimately critical to the team or organization’s success.

To Measure is to Know

Lord William Thomson Kelvin was a pretty smart guy who lived in the 1800s. He didn’t get everything right (e.g., he supposedly stated, “X-rays will prove to be a hoax.”), but his success ratio was far better than most, so he possessed useful insight. I’m a fan of his quote, “If you can not measure it, you can not improve it.”

Business Intelligence (BI) systems can be very powerful, but only when embraced as a catalyst for change. What you often find in practice is that the systems are not actively used or do not track the “right” metrics (i.e., those that highlight something important – ideally something leading – that you have the ability to adjust and impact the results), or provide the right information – only too late to make a difference.

The goal of any business is to develop a profitable business model and execute extremely well. So, you need to have something people want, deliver high-quality goods and/or services, and finally make sure you can do that profitably (it’s amazing how many businesses fail to understand this last part). Developing a systematic approach that allows for repeatable success is extremely important. Pricing at a competitive level with a healthy profit margin provides the means for sustainable growth.

Every business is systemic in nature. Outputs from one area (such as a steady flow of qualified leads from Marketing) become inputs to another (Sales). Closed deals feed project teams, development teams, support teams, etc. Great jobs by those teams will generate referrals, expansion, and other growth – and the cycle continues. This is an important concept because problems or deficiencies in one area can negatively affect others.

Next, the understanding of cause and effect is important. For example, if your website is not getting traffic, is it because of poor search engine optimization or bad messaging and/or presentation? If people visit your website but don’t stay long, do you know what they are doing? Some formatting is better for printing than reading on a screen (such as multi-column pages), so people tend to print and go. And external links that do not open in a new window can hurt the “stickiness” of a website. Cause and effect are not always as simple as they seem, but having data on as many areas as possible will help you identify which ones are important.

When I had my company, we gathered metrics on everything. We even had “efficiency factors” for every Consultant. That helped with estimating, pricing, and scheduling. We would break work down into repeatable components for estimating purposes. Over time we found that our estimates ranged between 4% under and 5% over the actual time required for nearly every work package within a project. This allowed us to profitably fix bid projects, which in turn created confidence for new customers. Our pricing was lean (we usually came in about the middle of the pack from a price perspective, but a critical difference was that we could guarantee delivery at that price). More importantly, it allowed us to maintain a healthy profit margin to hire the best people, treat them well, invest in our business, and create sustainable profitability.

There are many standard metrics for all aspects of a business. Getting started can be as simple as creating sample data based on estimates, “working the model” with that data, and seeing if this provides additional insight into business processes. Then ask, “When and where could I have made a change to positively impact the results?” Keep working until you have something that seems to work, then gather real data and validate (or fix) the model. You don’t need fancy dashboards (yet). When getting started, it is best to focus on the data, not the flash.

Within a few days, it is often possible to identify and validate the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that are most relevant to your business. Then, start consistently gathering data, systematically analyzing it, and then work on presenting it in a way that is easy to understand and drill-into in a timely manner. To measure the right things really is to know.

Acting like an Owner – Does it matter?

One of the biggest changes to my professional perspective on business came when I started my own consulting business. Prior to that, I had worked as an employee for midsize to large companies for ten years and then as one of the first hires at a start-up technology company. I felt that doing hands-on work, managing, selling, and helping establish a start-up (where I did not have an equity stake) provided everything needed to start my own business.

Well, guess what? I was only partially correct. I was prepared for the activities of running the business but really was not prepared for the responsibility of running a business. While this seems like it should be obvious, I’ve seen many business owners whose primary focus is on growth/upside activities and not the day-to-day. That type of optimism is important for entrepreneurs – without it, they would not bother putting so much at risk.

People tend to adopt a different perspective when making decisions once they realize that every action and decision can impact the money moving into and out of their own wallets.

Even in a large business, you can usually spot the people who have taken these risks and run their own business. I was responsible for a Global Business Unit with $60+ million in annual sales and ran it like a “business within a business.” Having P&L responsibilities meant the decisions I made mattered to my success and the success of my business unit.

It’s more than just striking out on your own as a contractor or sole proprietor. I’m talking about the people who have had employees, invested in capital equipment and went all-in. These are the people thinking about the big picture and the future.

What do these people do differently than those without this type of experience?

One of the biggest things is they view business as “good business” and “bad business.” Not all business is good business, and not all customers are good customers. There needs to be a fair commercial exchange where both sides receive value, mutual respect, and open communication. You know this works when your customers treat you like a true partner (a real trusted advisor) instead of just a vendor, or at least do not try to take advantage of you (and vice-versa).

A business is in business to make money, so if your work is not profitable, you should not do it. And, if you are not delivering value to an organization, it is very likely that you would be better off spending your time elsewhere – building your reputation and reference base within an organization that was a better fit. While that may not be true for all business endeavors (think how long it took Amazon to become profitable and where they are now), it generally is true for employees at all levels.

“Bad” salespeople (who may very well regularly exceed their quotas) only care about the sale and their commission – not the fit, the customer’s satisfaction, or the effort required to support that customer. Selling products and services people don’t need, charging too little or too much, and making promises they know will not be met are typical signs of a person who does not think like an owner. Their focus is on the short-term and not on growing accounts. As an aside, their compensation plans generally only reward net new business and first-time sales, not ongoing customer satisfaction, so these actions may not be completely their fault.

How you view and treat employees is another big difference. Unfortunately, even business owners do not always get this right. I believe that employees are either viewed as Assets (to be managed for growth and long-term value) or Commodities (to be used up and replaced as needed – usually treated as fungible, as if they are easily replaceable). Your business is usually only as good as your employees, so treating them well and with respect creates loyalty and results in higher customer satisfaction.

Successful business owners usually look for the best person out there, not just the most affordable person who is “good enough” to do the job. On the flip side, you quickly need to weed out the people who are not a good fit. Making good decisions quickly and decisively is often a hallmark of a successful business owner. The saying about hiring slowly and firing quickly makes even more sense when you are running a lean operation that requires every person to contribute to the success of the company.

Successful business owners are generally more innovative. They are willing to experiment and take risks. They reward that behavior. They understand the need to find a niche where they can win and provide goods and/or services tailored to those specific needs.

Sometimes, this means specialization and customization, and sometimes, it means personalized attention and better support. Regardless of what is different, these people observe the small details, understand their target market, and are good at defining a message articulating those differences. These are the people who seem to be able to see around corners and anticipate both problems and opportunities. They do this out of necessity.

Former business owners are usually more conscientious about money, taking a “my money” perspective on sales and expenses. Every dollar in the business provides safety and opportunity for growth. These usually are not the people who routinely spend hundreds or thousands of dollars on business meals or who take unnecessary or questionable trips to nice places. Money saved on unnecessary expenses can be invested in new products, features, or marketing for the benefit of an organization.

While these are common traits of successful business owners, you can develop them even if you have never owned a business.

When selling, are you focused on delivering value, developing a positive reputation within that organization and with your customers, and profiting from long-term relationships? When delivering services, is your focus on delivering what has been contracted – and doing so on time and within budget? Are your projects used as examples of how things should be done within other organizations? Are you spending money on the right things – not wasteful or extravagant things?

These are things employees at all levels can do. They will make a difference and help you stand out. That opens the door to career growth and change. And it may get you thinking about starting the business you have always dreamed of. Awareness and understanding are the first steps towards change and improvement.

- ← Previous

- 1

- …

- 8

- 9

- 10

- Next →