Business Ownership and Management

It’s not Rocket Science – What you Measure Defines how People Behave

I previously wrote a post titled “To Measure is to Know.”

The other side of the coin is that what you measure defines how people behave. This is an often forgotten aspect of Business Intelligence, Compensation Plans, Performance reviews, and other key areas in business. While many people view this topic as “common sense,” based on the numerous incentive plans you run across as a consultant and compensation plans you submit as a Manager, that is not the case.

Is it wrong to have people respond by focusing on specific aspects of their job that they are being measured on? That is a tricky question. This simple answer is “sometimes.” This is ultimately the desired outcome of implementing specific KPIs (key performance indicators), OKRs (objectives and key results), MBOs (Management by Objectives), and CSAT (Customer Satisfaction), but it doesn’t always work. Let’s dig into this a bit deeper.

One prime example is something seemingly easy yet often anything but – Compensation Plans. When properly implemented, these plans drive organic business growth through increased sales, revenue, and profits (three related items that should be measured). This can also drive steady cash flow by closing deals faster and within specific periods (usually months or quarters) and focusing on models that create the desired revenue stream (e.g., perpetual license sales versus subscription license sales versus SaaS subscription sales). What could be better than that?

Successful salespeople focus on the areas of their comp plan where they have the greatest opportunity to make money. Presumably, they are selling the products or services that you want them to based on that plan. MBO and OKR goals can be incorporated into plans to drive toward positive outcomes that are important to the business, such as bringing on new reference accounts. Those are forward-looking goals that increase future (as opposed to immediate) revenue. In a perfect world, with perfect comp plans, these business goals are codified and supported by motivational financial incentives.

Some of the most successful salespeople are the ones who primarily care only about themselves (although not at the expense of their company or customers). They are in the game for one reason—to make money. Give them a well-constructed plan that allows them to win, and they will do so in a predictable manner. Paying large commission checks should be a goal for every business because properly constructed compensation plans mean their own business is prospering. It needs to be a win-win design.

However, suppose a salesperson has a poorly constructed plan. In that case, they will likely find ways to personally win with deals inconsistent with company growth goals (e.g., paying a commission based on deal size but not factoring in profitability and discounts). Even worse, give them a plan that doesn’t provide a chance to win, and the results will be uncertain at best.

Just as most tasks tend to expand to use all the time available, salespeople tend to book most of their deals at the end of whatever period is used. With quarterly payment cycles, most of the business tends to book in the final week or two of the quarter, which is not ideal from a cash flow perspective. Using shorter monthly periods may increase business overhead. Still, the potential to level out the flow of booked deals (and associated cash flow) from salespeople working harder for that immediate benefit will likely be a worthwhile tradeoff. I pushed for this change while running a business unit, and we began seeing positive results within the first two months.

What about motiving Services teams? What I did with my company was to provide quarterly bonuses based on overall company profitability and each individual’s contribution to our success that quarter. Most of our projects used task-oriented billing, where we billed 50% up-front and 50% at the time of the final deliverables. You needed to both start and complete a task within a quarter to maximize your personal financial contribution, so there was plenty of incentive to deliver and quickly move to the next task. As long as quality remains high, this is a good thing.

We also factored in salary costs (i.e., if you make more than you should be bringing in more value to the company), the cost of re-work, and non-financial items that were beneficial to the company. For example, writing a white paper, giving a presentation, helping others, or even providing formal documentation on lessons learned added business value and would be rewarded. Everyone was motivated to deliver quality work products in a timely manner, help each other, and do things that promoted the growth of the company. My company prospered, and my team made good money to make that happen. Another win-win scenario.

This approach worked very well for me and was continually validated over several years. It also fostered innovation because the team was always looking for ways to increase their value and earn more money. Many tools, processes, and procedures emerged from what would otherwise be routine engagements. Those tools and procedures increased efficiency, consistency, and quality. They also made it easier to onboard new employees and incorporate an outsourced team for larger projects.

Mistakes with comp plans can be costly – due to excessive payouts and/or because they are not generating the expected results. Backtesting is one form of validation as you build a plan. Short-term incentive programs are another. Remember, without some risk, there is usually little reward, so accept that some risk must be taken to find the point where the optimal behavior is fostered and then make plan adjustments accordingly.

It can be challenging and time-consuming to identify the right things to measure, the proper number of things (measuring too many or too few will likely fall short of goals), and provide the incentives to motivate people to do what you want and need. But, if you want your business to grow and be healthy, it must be done well.

This type of work isn’t rocket science and is well within everyone’s reach.

Are you Visionary or Insightful?

Having great ideas that are not understood or validated is pointless, just as being great at “filling in the gaps” to do amazing things does not accomplish much if what you are building achieves little toward your needs and goals. This post is about Dreaming Big and turning those dreams into actionable plans.

Let me preface this post by stating that both are important and complementary roles. But, if you don’t recognize the difference between the two, it becomes much more challenging to execute and realize value/gain a competitive advantage.

The Visionary has great ideas but doesn’t always create plans or follow through on developing the idea. There are many reasons why this happens (distractions, new interests, frustration, lack of time), so it is good to be aware of that, as this type of person can benefit by being paired with people willing and able to understand a new idea or approach, and then take the next steps to flesh out a high-level plan to present that idea and potential benefits to key stakeholders. People may view them as aloof or unfocused.

The Insightful sees the potential in an idea, helps others understand the benefits and gain their support, and often creates and executes a plan to prototype and validate the idea – killing it off early if the anticipated goals are unachievable. They document, learn from these experiences, and become more and more proficient with validating the idea or approach and quantifying the potential benefits. They are usually very pragmatic.

Neither of these types of people is affected by loss aversion bias.

I find it amazing how frequently you hear someone referred to as being Visionary, only to see that the person in question could eliminate some of the noise and “see further down the road” than most people. While this skill is valuable, it is more akin to analytics and science than art. Insight usually comes from focus, understanding, intelligence, and being open-minded. Those qualities matter in both business and personal settings.

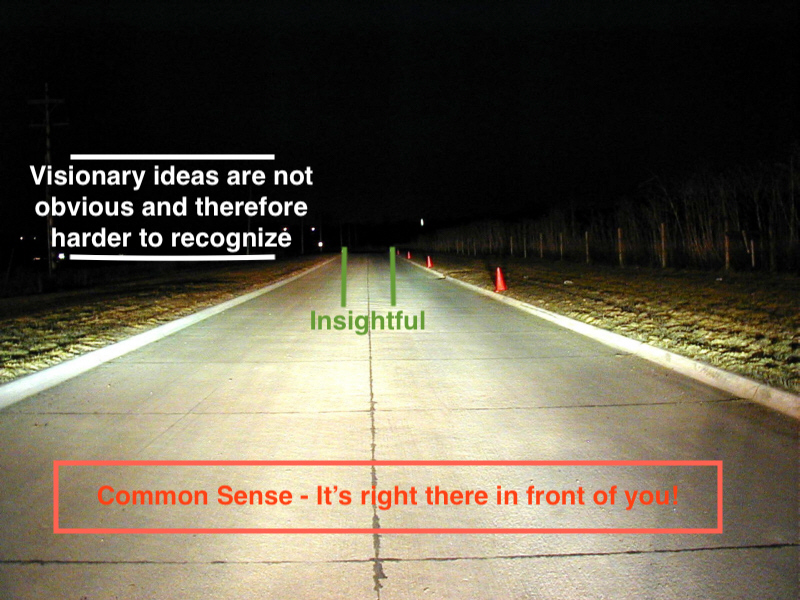

On the other hand, someone truly visionary looks beyond what is already illuminated and can, therefore, be detected or analyzed. It’s like a game of chess where the visionary person is thinking six or seven moves ahead. They are connecting the dots for the various future possibilities while their competitor is still thinking about their next move.

Interestingly, this can be a very frustrating situation for everyone.

- The Visionary with an excellent idea may become frustrated because they feel an unmet need to be understood.

- The people around that visionary person become frustrated, wondering why that person isn’t able to focus on what is important or why they fail to see/understand the big picture.

- Others view the visionary ideas and suggestions as tangential or irrelevant. It is only over time that the others understand what the visionary person was trying to show them – often after a competitor has started executing a similar idea.

- The Insightful wanting to make a difference can feel constrained in static environments, offering little opportunity for change and improvement.

Both Insightful and Visionary people feel that they are being strategic. Both believe they are doing the right thing. Both have similar goals. What’s truly ironic is they may view each other as the competition rather than seeing the potential of collaborating.

A strong management team can positively impact creativity by fostering a culture of innovation and placing these people together to work towards a common goal. Providing little time and resources to explore an idea can lead to remarkable outcomes. When I had my consulting company, I sometimes joked, “What would Google do?” to describe that amazing things were possible and waiting to be done.

The insightful person may see a payback on their ideas sooner than the visionary person, and that is due to their focus on what is already in front of them. It may be a year or more before what the visionary person has described shifts to the mainstream and into the realm of insight – hopefully before it reaches the realm of common sense (or worse yet, is entirely passed by).

I recommend that people create a system to gather ideas, along with a description of what the purpose, goals, and advantages of those ideas are. Foster creative behavior by rewarding people for participation regardless of what becomes of the idea. Review those ideas regularly and document your commentary. You will find good ideas with luck – some insightful and possibly even visionary.

Look for commonalities and trends to identify the people who can cut through the noise or see beyond the periphery and the areas having the greatest innovation potential. This approach will help drive your business to the next level.

You never know where the next good idea will come from. Efforts like these provide growth opportunities for people, products, and profits.

Investing in Others – Becoming a Mentor

I have been very fortunate throughout my career. There have been incredible opportunities, risks with big rewards, and lessons learned from mistakes and failure (e.g., one of the biggest lessons learned early is that most mistakes will not kill you, and therefore you can find a way to recover from them). In hindsight, the people who saw something in me and invested in my career – my mentors – have been most valuable in shaping my career.

None of these people had to help me. It’s possible that they did so for their own benefit (i.e., the better I do my job, the easier it is for them), but I believe they were passing along a valuable gift. I was lucky to have been given these gifts early in my career, as they have been invaluable personally and professionally.

As a mentee may not recognize either the value of what you are receiving, or the effort that has gone into providing that gift to you. You fully appreciate what others have done for you only years later.

In my first programming job, my manager (Jim) assigned me to work with different key people and would follow up every time to ask what I had learned. One day he gave me my first project. I was excited but anxious because I did not want to fail my mentor.

I only had six months of experience, and this was a big project for an important automotive customer (Subaru, for the first fully customized customer loyalty coupon system for a major auto manufacturer in the late 1980s). It was a stretch for me, and the system had to be production-ready in six months.

Jim let me build it, checked daily to see if I had questions, and would provide feedback and direction if I asked. Aside from that he pretty much left me alone. He seemed more confident in my ability to succeed than I did at the time.

After two months, I thought I was finished. We reviewed everything, and Jim constructively picked apart my system – pointing out various flaws and then discussing the logic and reasoning behind my decisions. We spent half a day on this exercise, and it was only years later I realized that he was helping me learn more than simply validating the system design.

After another two months, we reviewed this system’s second iteration. He told me while this version would work and would be acceptable from anyone else, I still had time remaining, and he was confident that I could do even better next time. He provided a couple of tips about high-level areas he focused on while designing and developing systems and left it at that.

When I returned with the third iteration system, he reviewed it, smiled, and said he could not have done this better himself. At first, I was proud of completing my first independent project, but later I realized how much I had learned in those six months. This experience provided me with a lifelong benefit as well as provided the motivation to help others in a similar manner. My mentor was (and still is) a great leader!

As a manager this person had so many reasons not to give me the project, to just tell me what to do, and to not let me redo it (twice). From a short-term management perspective, what he did was wasteful. But, from a big-picture perspective, he was doing things that helped me create more value for the company for the 3-4 years I continued working there. The benefits outweighed the cost; Jim was wise enough to see that.

Several years ago, a young woman in Australia contacted me via LinkedIn, asking for suggestions on improving her skills to advance her career. I gave her many assignments over a year and she did amazing work. She advanced in her company, later relocated to another country, and then switched industries. She currently holds a high-level position and has been very successful. It made me feel good knowing that my efforts played a small part in her advancement.

From my perspective, it all comes down to how you view people and relationships. Are they like commodities that are used and replaced as needed, or are they assets that can grow in value? I like to think that I have helped several people’s “career portfolios,” which helps ensure that business is not a zero-sum game. Hopefully, those people will do the same thing, increasing leverage on those investments that started with Jim.

So, what do you think?

Failing Productively

As an entrepreneur, you will typically get advice like, “Fail fast and fail often.” I always found this somewhat amusing, similar to the saying, “It takes money to make money” (a lot of bad investments are made using that philosophy). Living this yourself is an amazing experience – especially when things turn out well. But as I have written about before, you learn as much from the good experiences as you do from the bad ones.

Innovating is tough. You need people who always think of different and better ways of doing things or question why something has to be done or made a certain way. It means shifting away from the “how” and “why” and focusing on the “what” (outcomes). It takes confidence to ask questions that many would view as stupid (“Why would you do that, it’s always been done this way.”) But, when you have the right mix of people and culture, amazing things can and do happen, and it feels great.

Innovating also takes a willingness to lose time and money, hoping to win something big enough later to make it all worthwhile. This is where many companies fall short because they lack the patience, budget, or appetite to fail. I personally believe that this is the reason why innovation often flows from small companies and small teams. For them, the prospect of doing something cool or making a big impact is motivation enough to try something, and the barriers to getting started are often much lower.

It takes a lot of discipline to follow a plan when a project appears to be failing, but it takes even more discipline to kill a project that has demonstrated real potential but isn’t meeting expectations. That was one of my first and probably most important lessons learned in this area. Let me explain…

In 2000 we looked at franchising our “Consulting System” – processes, procedures, tools, metrics, etc., developed and proven in my business. We believed this approach could help average consultants deliver above-average work products in less time. The idea seemed to have real potential.

Finding an attorney who would even consider this idea took a lot of work. Most believed it would be impossible to proceduralize a somewhat ambiguous task like solving a business or technical problem. We finally found an attorney who, after a 2-hour no-cost interview, agreed to work with us. When asked about his approach, he replied, “I did not want to waste my [his] time or our money on a fool’s errand.”

We estimated it would take 12 months and cost approximately $100,000 to fully develop our consulting system. We met with potential prospects to validate the idea (it would have been illegal to pre-sell the system) and then got to work. Twelve months turned into 18, and the original $100K budget increased nearly 50%. All indications were positive, and we felt very good about the success and business potential of this effort.

Then, the terror attacks occurred on Sept. 11th and businesses everywhere saw a decline. In early 2002 we reevaluated the project and felt that it could be completed within the next 6-8 months and would cost another $50K+.

After a long and emotional debate, we decided to kill the project – not because we felt it would not work, but because there was less of a target market, and now the payback period (time to value) would double or triple. This was one of the most difficult business decisions that I ever made.

A big lesson learned from this experience was that our approach needed to be more analytical.

- From that point forward, we created a budget for “time off” (we bought our own time, as opposed to waiting for bench time) and other project-related items.

- We developed a simple system for collecting and tracking ideas and feedback. When an idea felt right, we would take the next steps and create a plan with a defined budget, milestones, and timeline. If the project failed to meet any defined objectives, it would be killed – No questions asked.

- We documented what we did, why we decided to do it, our goals, and expected outcomes and timelines. Regardless of success or failure, we would conduct postmortem reviews to learn and document as much as possible from every effort and investment.

We still had failures, but with each one, we took less time and spent less money. More importantly, we learned how to do this better, which helped us realize several successes. It provided both the structure and the freedom to create some amazing things. Since failing was an acceptable outcome, it was never feared.

This approach was more than just “failing fast and failing often”; it was “intelligent failure,” which served us well for nearly a decade.

Profitability through Operational Efficiency

In my last post, I discussed the importance of proper pricing for profitability and success. As most people know, you increase profitability by increasing revenue and/or decreasing costs. However, cost reduction does not necessarily mean slashing headcount, wages, benefits, or other factors that often negatively affect morale and cascade negatively on quality and customer satisfaction. There is often a better way.

The best businesses generally focus on repeatability and reliability, realizing that the more you do something – the better you should get at doing it well. You develop a compelling selling story based on past successes, develop a solid reference base, and have identified the sweet spot from a pricing perspective. People keep buying what you are selling, and if your pricing is right, money is available at the end of the month to fund organic growth and operational efficiency efforts.

Finding ways to increase operational efficiency is the ideal way to reduce costs, but it takes time and effort. Sometimes this is realized through increases in experience and skill. But, often optimization occurs through standardization and automation. Developing a system that works well, consistently applying it, measuring and analyzing the results, and then making changes to improve the process. An added benefit is that this approach increases quality, making your offering even more attractive.

Metrics should be collected at a “work package” level or lower (e.g., task level), which means they are related tasks at the lowest level that produce a discrete deliverable. This project management concept works whether you are manufacturing something (although a Bill of Materials may be a better analogy in this segment), building something, or creating something. This allows you to accurately create and validate cost and time estimates. When analyzing work at this level of detail, it becomes easier to identify ways to simplify or automate the process.

When I had my company, we leveraged this approach to win more business with competitive fixed-price project bids that provided healthy profit margins for us while minimizing risk for our clients. Bigger profit margins allowed us to invest in our own growth and success by funding ongoing employee training and education, innovation efforts, and international expansion, as well as experimenting with new things (products, technology, methodology, etc.) that were fun and often taught us something valuable.

Those growth activities were only possible because we focused on doing everything as efficiently and effectively as possible, learning from everything we did – good and bad, and having a tangible way to measure and prove that we were constantly improving.

Think like a CEO, act like a COO, and measure like a CFO. Do this and make a real difference in your own business!