leadership

Never Panic!

Panic is not a good problem-solving tool, regardless of your position or role. It is especially bad when you are in charge of people or brought in for your expertise. Panic leads to a myopic view of the problem, hindering creativity.

The point in my career when this became readily apparent was when I was working for a small software company. We had a new product (Warehouse Management System) and were launching our third deployment. This one was more complicated than the rest because it was for a pharmaceutical company. In addition to requirements like refrigeration and lot control, there was a mix of FDA-controlled items requiring various forms of auditing and security and storage areas significantly smaller than previous installations. It was a challenge, to be sure.

A critical component, “Location Search,” failed during this implementation. About 10-12 people were in the “war room” when my boss, the VP of Development, began to panic. He was extremely talented and normally did an excellent job, but his reaction negatively affected the others in the room. The mood quickly worsened.

I jumped in and took over because I did not want to be stuck there all weekend and mostly because I wanted this implementation to succeed. I asked my boss to go out and get a bunch of pizzas. Next, I organized a short meeting to review what we knew and what was different from our prior tests and asked for speculation about the root cause of this problem. The team came up with two potential causes and one potential workaround. Everyone was organized into three teams, and we began attacking each item independently and in parallel.

We identified the root cause, which led to an ideal fix a few days later and a workaround that allowed us to finish the user acceptance testing and go live the following day. A change in mindset fostered the collaboration and problem-solving needed to move forward.

But this isn’t just limited to groups. I was a consultant at a large insurance company on a team redesigning their Risk Management system. We were using new software and wanted to be sure that the proper environment variables were set during the Unix login process for this new system. I volunteered to create an external function executed as part of the login process. Trying to maintain clean code, I had an “exit” at the end of the function. It worked well during testing, but once it was placed into production, the function immediately logged people out as they attempted to log into the system.

As you can imagine, I had a sinking feeling in my gut. How could I have missed this? This was a newer system deployed just for this risk management application, so no other privileged users were logged in at the time. Then, I remembered reading about a Unix “worm” that used FTP to infiltrate systems. The article stated that FTP bypassed the standard login process. This allowed me to FTP into the system and then delete the offending function. In less than 5 minutes, everything was back to normal.

A related lesson learned was to make key people aware of what happened, noting that the problem had been resolved and that there was no lasting damage. Hiding mistakes kills careers. Then, we created a “Lessons Learned” log, with this as the first entry, to foster the idea of sharing mistakes to avoid them in the future. Understanding that mistakes can happen to anyone is a good way to get people to plan better and keep them from panicking when problems occur.

Staying calm and focused on resolving the problem is a much better approach than worrying about blame and the implications of those actions. And most people appreciate the honesty.

As the novelist James Lane Allen stated, “Adversity does not build character; it reveals it.”

The Value Created by a Strong Team

I participated in an amazing team-building exercise as a Board Member for the Children’s Hospital Foundation of Wisconsin. We were going down a path that led to a decision on whether or not to invest $150M in a new addition. The CEO at the time, Jon Vice, wisely determined that strong teams were needed for each committee in order to thoroughly vet the idea from every possible perspective.

The process started with being given a book to read (“Now, Discover Your Strengths” by Marcus Buckingham & Donald O. Clifton, Ph.D.) and then completing the “Strengthsfinder” assessment using a code provided in the book. The goal was to understand gaps in perception (how you view yourself vs. how others view you) so that you could truly understand your own strengths and weaknesses. Then, teams were created with people having complementary skills to help eliminate weaknesses from the overall team perspective. The results were impressive.

Over my career, I have been involved in many team-building exercises and events – some of which provided useful insights. However, most failed to combine the findings meaningfully, provide useful context, or offer actionable recommendations. Key areas that were consistently omitted were Organizational Culture, Organizational Politics, and Leadership. Those three areas significantly impact value creation vis-à-vis team effectiveness and commitment.

When I had my consulting company, we had a small core team of business and technology consultants and would leverage subcontractors and an outsourcing company to allow us to take on more concurrent projects as well as larger, more complex projects. This approach worked for three reasons:

- We had developed a High-Performance Culture that was based on:

- Purpose: A common vision of success, understanding why that mattered, and understanding how that was defined and measured.

- Ownership: Taking responsibility for something and being accountable for the outcome. This included responsibility for the extended team of contractors. Standardized procedures helped ensure consistency and make it easier for each person to accept responsibility for “their team.”

- Trust: Everyone understood that they not only needed to trust and support each other, but in order to be effective and responsive, the others would need to trust their judgment. If there was a concern, we would focus on the context and process improvements to understand what happened and implement changes based on lessons learned. Personal attacks were avoided for the good of the entire team.

- Empowerment: Everyone understood that there was risk associated with decision-making while at the same time realizing that delaying an important decision could be costly and create more risk. Therefore, it was incumbent upon each member to make good decisions as needed and then communicate changes to the rest of the team.

- Clear and Open Communication: The people on the team were very transparent and honest. When there was an issue, they would attempt to resolve it first with that person and then escalate if they could not reach an agreement and decided to seek the team’s consensus. Everything was out in the open and done in the spirit of being constructive and collaborating. Divisiveness is the antithesis of this tenet.

People who were not a good fit would quickly wash out, so our core team consisted of trusted experts. A friendly competition helped raise the bar for the entire team, but when needed, the other team members became a safety net for each other.

We were all focused on the same goal, and everyone realized that the only way to be successful was to work together for the team’s success. Win or lose, we did it together. The strength of our team created tremendous value – internally and for our customers that we sustained for several years. That value included innovation, higher levels of productivity and profitability, and an extremely high success rate.

This approach can work at any level but is most effective when it starts at the top. When employees see their company leaders behaving in this manner, it provides the model and sets expectations for everyone under them. If there is dysfunction within an organization, it often starts at the top – by promoting or accepting behaviors that do not benefit the whole of the organization. But, with a strong and positive organizational culture, the value of strong teams is multiplied and becomes an incredible competitive advantage.

Are you Visionary or Insightful?

Having great ideas that are not understood or validated is pointless, just as being great at “filling in the gaps” to do amazing things does not accomplish much if what you are building achieves little toward your needs and goals. This post is about Dreaming Big and turning those dreams into actionable plans.

Let me preface this post by stating that both are important and complementary roles. But, if you don’t recognize the difference between the two, it becomes much more challenging to execute and realize value/gain a competitive advantage.

The Visionary has great ideas but doesn’t always create plans or follow through on developing the idea. There are many reasons why this happens (distractions, new interests, frustration, lack of time), so it is good to be aware of that, as this type of person can benefit by being paired with people willing and able to understand a new idea or approach, and then take the next steps to flesh out a high-level plan to present that idea and potential benefits to key stakeholders. People may view them as aloof or unfocused.

The Insightful sees the potential in an idea, helps others understand the benefits and gain their support, and often creates and executes a plan to prototype and validate the idea – killing it off early if the anticipated goals are unachievable. They document, learn from these experiences, and become more and more proficient with validating the idea or approach and quantifying the potential benefits. They are usually very pragmatic.

Neither of these types of people is affected by loss aversion bias.

I find it amazing how frequently you hear someone referred to as being Visionary, only to see that the person in question could eliminate some of the noise and “see further down the road” than most people. While this skill is valuable, it is more akin to analytics and science than art. Insight usually comes from focus, understanding, intelligence, and being open-minded. Those qualities matter in both business and personal settings.

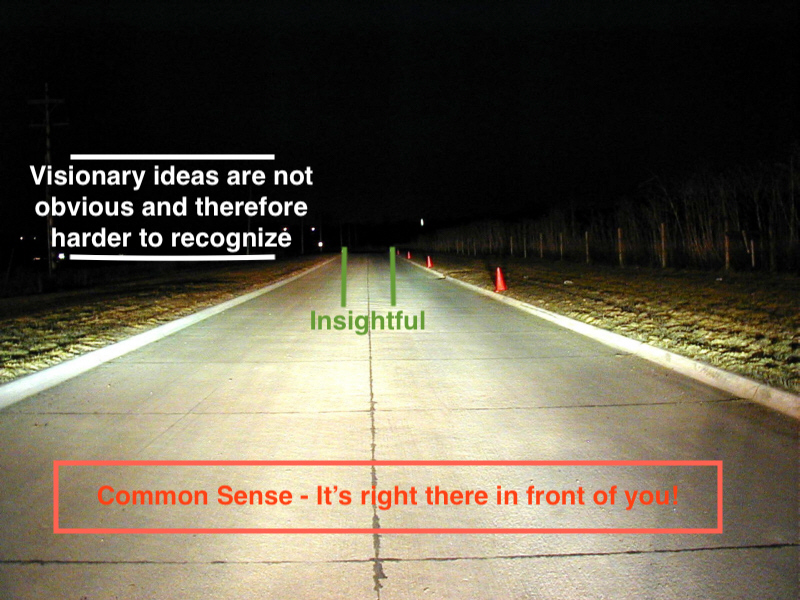

On the other hand, someone truly visionary looks beyond what is already illuminated and can, therefore, be detected or analyzed. It’s like a game of chess where the visionary person is thinking six or seven moves ahead. They are connecting the dots for the various future possibilities while their competitor is still thinking about their next move.

Interestingly, this can be a very frustrating situation for everyone.

- The Visionary with an excellent idea may become frustrated because they feel an unmet need to be understood.

- The people around that visionary person become frustrated, wondering why that person isn’t able to focus on what is important or why they fail to see/understand the big picture.

- Others view the visionary ideas and suggestions as tangential or irrelevant. It is only over time that the others understand what the visionary person was trying to show them – often after a competitor has started executing a similar idea.

- The Insightful wanting to make a difference can feel constrained in static environments, offering little opportunity for change and improvement.

Both Insightful and Visionary people feel that they are being strategic. Both believe they are doing the right thing. Both have similar goals. What’s truly ironic is they may view each other as the competition rather than seeing the potential of collaborating.

A strong management team can positively impact creativity by fostering a culture of innovation and placing these people together to work towards a common goal. Providing little time and resources to explore an idea can lead to remarkable outcomes. When I had my consulting company, I sometimes joked, “What would Google do?” to describe that amazing things were possible and waiting to be done.

The insightful person may see a payback on their ideas sooner than the visionary person, and that is due to their focus on what is already in front of them. It may be a year or more before what the visionary person has described shifts to the mainstream and into the realm of insight – hopefully before it reaches the realm of common sense (or worse yet, is entirely passed by).

I recommend that people create a system to gather ideas, along with a description of what the purpose, goals, and advantages of those ideas are. Foster creative behavior by rewarding people for participation regardless of what becomes of the idea. Review those ideas regularly and document your commentary. You will find good ideas with luck – some insightful and possibly even visionary.

Look for commonalities and trends to identify the people who can cut through the noise or see beyond the periphery and the areas having the greatest innovation potential. This approach will help drive your business to the next level.

You never know where the next good idea will come from. Efforts like these provide growth opportunities for people, products, and profits.

Investing in Others – Becoming a Mentor

I have been very fortunate throughout my career. There have been incredible opportunities, risks with big rewards, and lessons learned from mistakes and failure (e.g., one of the biggest lessons learned early is that most mistakes will not kill you, and therefore you can find a way to recover from them). In hindsight, the people who saw something in me and invested in my career – my mentors – have been most valuable in shaping my career.

None of these people had to help me. It’s possible that they did so for their own benefit (i.e., the better I do my job, the easier it is for them), but I believe they were passing along a valuable gift. I was lucky to have been given these gifts early in my career, as they have been invaluable personally and professionally.

As a mentee may not recognize either the value of what you are receiving, or the effort that has gone into providing that gift to you. You fully appreciate what others have done for you only years later.

In my first programming job, my manager (Jim) assigned me to work with different key people and would follow up every time to ask what I had learned. One day he gave me my first project. I was excited but anxious because I did not want to fail my mentor.

I only had six months of experience, and this was a big project for an important automotive customer (Subaru, for the first fully customized customer loyalty coupon system for a major auto manufacturer in the late 1980s). It was a stretch for me, and the system had to be production-ready in six months.

Jim let me build it, checked daily to see if I had questions, and would provide feedback and direction if I asked. Aside from that he pretty much left me alone. He seemed more confident in my ability to succeed than I did at the time.

After two months, I thought I was finished. We reviewed everything, and Jim constructively picked apart my system – pointing out various flaws and then discussing the logic and reasoning behind my decisions. We spent half a day on this exercise, and it was only years later I realized that he was helping me learn more than simply validating the system design.

After another two months, we reviewed this system’s second iteration. He told me while this version would work and would be acceptable from anyone else, I still had time remaining, and he was confident that I could do even better next time. He provided a couple of tips about high-level areas he focused on while designing and developing systems and left it at that.

When I returned with the third iteration system, he reviewed it, smiled, and said he could not have done this better himself. At first, I was proud of completing my first independent project, but later I realized how much I had learned in those six months. This experience provided me with a lifelong benefit as well as provided the motivation to help others in a similar manner. My mentor was (and still is) a great leader!

As a manager this person had so many reasons not to give me the project, to just tell me what to do, and to not let me redo it (twice). From a short-term management perspective, what he did was wasteful. But, from a big-picture perspective, he was doing things that helped me create more value for the company for the 3-4 years I continued working there. The benefits outweighed the cost; Jim was wise enough to see that.

Several years ago, a young woman in Australia contacted me via LinkedIn, asking for suggestions on improving her skills to advance her career. I gave her many assignments over a year and she did amazing work. She advanced in her company, later relocated to another country, and then switched industries. She currently holds a high-level position and has been very successful. It made me feel good knowing that my efforts played a small part in her advancement.

From my perspective, it all comes down to how you view people and relationships. Are they like commodities that are used and replaced as needed, or are they assets that can grow in value? I like to think that I have helped several people’s “career portfolios,” which helps ensure that business is not a zero-sum game. Hopefully, those people will do the same thing, increasing leverage on those investments that started with Jim.

So, what do you think?

Diamonds or just Shiny Rocks?

During a very candid review years ago, my boss at the time (the CEO of the company) made a surprising comment to me. He said, “Good ideas can be like diamonds – drop them occasionally, and they have a lot of value. But sprinkle them everywhere you go, and they just become a bunch of shiny rocks.” This was not the type of feedback that I was expecting, but it turned out to be both insightful and very valuable.

For a long time, I have held the belief that there are four types of people at any company: 1) People who want to make things better; 2) People who are interested in improvement but only in a supporting role; 3) People who are mainly interested in themselves (they can do great things, but often at the expense of others); and 4) People that are just there and don’t care much about anything. This opinion is based on working and consulting at many companies over a few decades.

A recent Gallup Poll stated Worldwide only 13% of Employees are “engaged at work” (the rest are “not engaged” or “actively disengaged”). This is a sad reflection of employees and work environments if it is true. Since it is a worldwide survey, it may be highly skewed by region or industry and, therefore, not indicative of what is typical across the board. Those results were not completely aligned with my thinking but were interesting nonetheless.

So, back to the story…

Before working at this company, I had run my own business for nearly a decade and was a consultant for 15 years, working at large corporations and startups. I am used to taking the best practices learned from other companies and engagements and incorporating them into our business practices to improve and foster growth.

I take a systemic view of business and see the importance of optimizing all components of “the business machine” to work harmoniously. Improvements in one area ultimately positively impact other areas of the business. From my naive perspective, I was helping everyone by helping those who have easily solved problems.

I learned that while trying to be helpful, I was insensitive to the fact that my “friendly suggestions based on past success” stepped on other people’s toes, creating frustration for those I intended to help. Providing simple solutions to their problems reflected poorly on my peers.

Suggestions and examples that were intended to be helpful had the opposite effect. Even worse, it was probably just as frustrating to me to be ignored as it was to others to have me infringe on their aspect of the business. The resulting friction was very noticeable to my boss.

Those ideas (“diamonds”) may have been considered had I been an external consultant. But as part of the leadership team, I was coming across as someone just interested in themselves (leaving “shiny rocks” laying around for people to ignore or possibly trip over).

Perception is reality, and my attempts to help were hurting me. Luckily, I received this honest and helpful feedback early in this position and was able to turn those perceptions around.

What are the morals of this story?

First, people who are engaged have the greatest potential to make a difference. Part of being a business leader is making sure that you have the best possible team, and are creating an environment that challenges, motivates, and fosters growth and accountability.

Disengaged employees or people who are unwilling or unable to work with/collaborate with others may not be your best choices, regardless of their talent. They could actually be detrimental to the overall team dynamics.

Second, doing what you believe to be the right thing isn’t necessarily the best or right way to approach something. Being sensitive to the big picture and testing whether or not your input is being viewed as constructive was a big lesson learned for me. If you have good ideas but are ineffective, consider that your execution could be flawed. Self-awareness is very important.

Third, use your own examples as stories to help others understand potential solutions to problems non-threateningly. Let them connect to their own problems, helping them become more effective and allowing them to save face. It is not a competition. And, if someone else has good ideas, help support them through collaboration. In the end, it should be more about effectiveness, growth, and achievement of business goals than who gets the most credit.

While this seems like common sense now, my background and personal biases blinded me to that perspective.

My biggest lesson learned was about adaptation. There are many ways to be effective and make a difference. Focus on understanding the situation and its dynamics to employ the best techniques, which is ultimately critical to the team or organization’s success.

- ← Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- Next →